MOMENTOUS EVENTS IN TIME

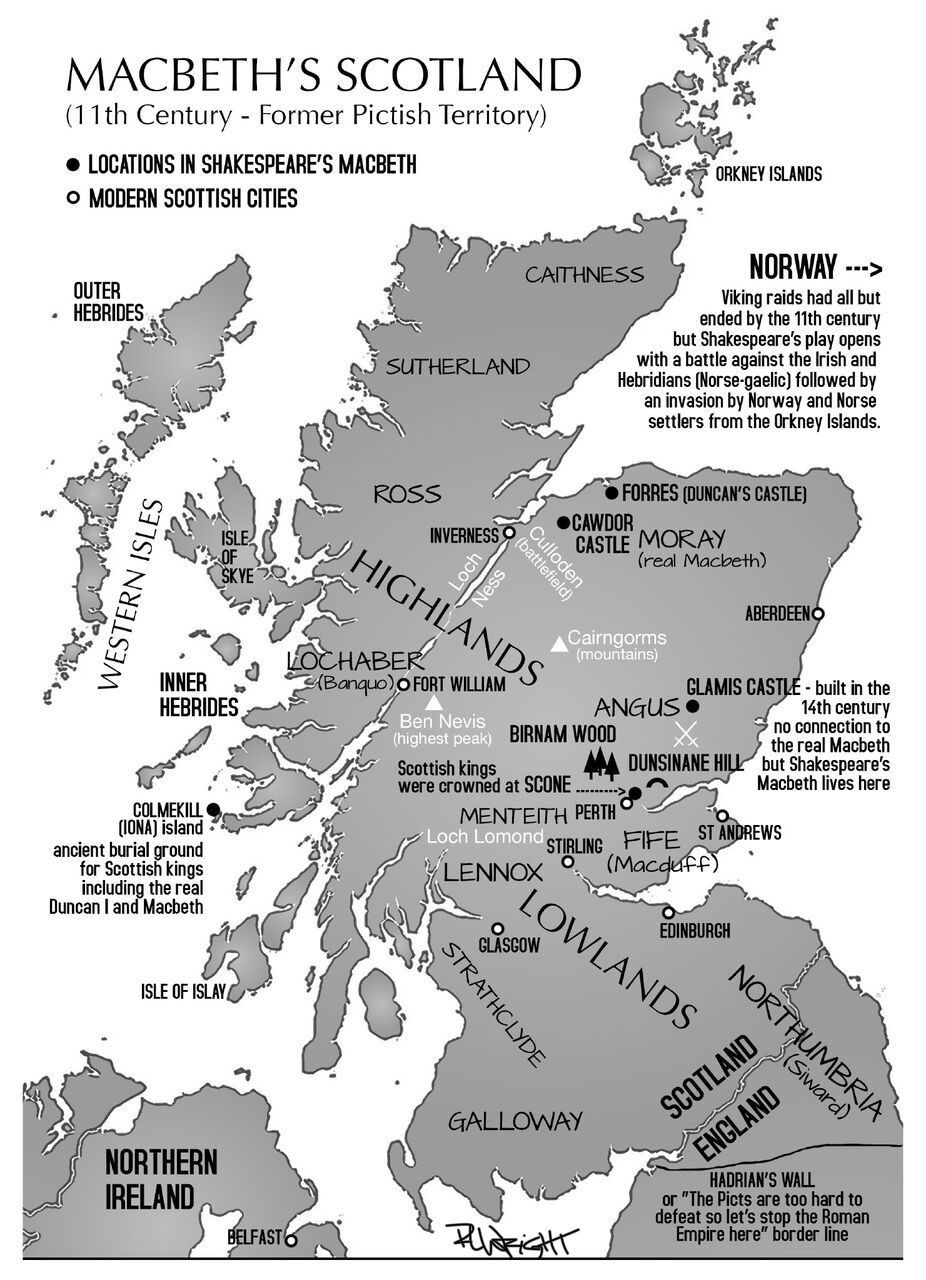

Today on the Historical Writers Summer Blog Hop, I’m taking you to Scotland in the 11th century to the world of Macbeth – but not Shakespeare’s Macbeth, the REAL Macbeth as far as we know him. As far back as 1054, even pre Conquest England was not averse to interfering in the business of its Scottish neighbours in the north. The Battle of the Seven Sleepers was one of these events which was to completely change the politics of the time in both countries and tragically led to the sad demise of the man called Macbeth, long vilified as a villain of Shakespeare. Here I discuss how the battle came about and what affect it had consequently.

The Protagonists

Scotland in the earlier half of the eleventh century was a hothouse of different factions vying for supremacy. The chief king, Malcolm II of the House of Alpin was without male sons in 1034 when he died. He had three grandsons, all of whom may have been in the running for kingship: Duncan, Thorfinn, and Macbeth. All were sons of Malcolm’s three daughters. Malcolm named Duncan as his heir, and this might have led to resentment amongst the remaining grandsons and their supporters.

One can imagine the three boys growing up at their grandfather’s court like brothers, in happy camaraderie and may have been close until 1034. Thorfinn, who was known as the Mighty, was ruler in the Orkneys from an early age after the death of his father Sigurd. Later, the lordship of Caithness was endowed upon him by his Scottish grandfather who obviously wanted him to have some influence in the mainland. MacBeth had to fight for his own success it seems, for his father, Findlaech, had been cruelly, but not unusually for this time, murdered by a cousin, Gillacomgain and took the Mormaership in Moray that had once belonged to Macbeth’s father. Macbeth wasn’t having this, and he in turn murdered the killer of his father in revenge, married, either with or without her consent, Gruoch, wife of the now deceased Gillacomgain. Gruoch was also of royal descent and also had a claim to the throne through her mother so if Macbeth had his eye on the kingship, his marriage to her would strengthen both their claims.

So, the cousins, who might have once been close like brothers, were now divided. Duncan alienated himself from them by unsuccessfully attacking Thorfinn – according to the Orkneyinga Saga, where he is identified as Karl Hundason. This was either before or after he went south with an army to attack Durham in retaliation for a Northumbrian ravaging of Cumbria. Durham was too far south from his own bases to be of any strategic use to Scotland so it was rather a reckless decision and not only that, the attack caused him to lose many of his cavalry. Adding this to his list of unsuccesses, Duncan rode north, hearing about a rising rebellion amongst the people of Moray who were unhappy with Duncan’s rule. Duncan seemed determined to redeem his military reputation at any cost. Evidently Thorfinn was to join forces with MacBeth in this, surprising Duncan, and a battle was fought where Duncan’s death ensued, , allowing Macbeth to seize power. Thorfinn must have been content or too busy with his position in Caithness and the Orkneys to challenge MacBeth’s claim.

Malcolm Canmore was Duncan’s eldest son, perhaps only a boy of eight or nine at the time of his father’s death, and he was spirited away with other members of Duncan’s family to safety, spending the years of MacBeth’s rule until 1054, growing up in England, perhaps at his kinsman’s Siward’s base in Northumbria, and at the court of Edward the Confessor. It is said that he was related to Earl Siward in some way, though how it is not clear. Malcolm’s father, Duncan, had links in Northumbria, having married a cousin or sister of Siward. It is not clear what exactly the link was, but whatever it was, Siward was willing to lead an army of Anglo-Danes into Scotland to supplant the man who usurped his kinsman’s crown. This might also have had something to do with Edward and Siward plotting to put in place a puppet king over Scotland to mitigate Scottish incursions over the border. And of course there was still the question of Cumbria and the dispute over territory.

The Battle

The battle of the Seven Sleepers, later known as the Battle of Dunsinane, took place on the 27th July 1054 – the day of the festival it was named for. No doubt, sponsored by his kinsman, Siward, Malcolm petitioned King Edward for support in his quest to take an army into Scotland to oust the usurper, Macbeth, and to reclaim his father’s crown. Edward was agreeable to send men from his own household guard, suggesting that such an investment in the war meant there was something in it for the English other than a willingness to support a hard-done-by young man. Edward never ventured further than Oxford in his lifetime as king and may not have worried too much about the north unless it was to affect his rule in the south; it was Siward who would benefit the most from Edward’s help. However, as king, it was Edward’s duty to support his vassals, and without Siward safe in the north, he could have turned on his English overlord making things very difficult for the south.

“This year went Siward the earl with a great army into Scotland, both with a ship-force and with a landforce, and fought against the Scots, and put to flight the king Macbeth, and slew all who were the chief men in the land, and led thence much booty, such as no man before had obtained. But his son Osbeorn, and his sister’s son Siward, and some of his housecarls, and also of the king’s, were there slain, on the day of the Seven Sleepers”

The Anglo Saxon Chronicle D

According to Symeon of Durham, Siward’s Anglo-Danish forces were made up of horse, and a powerful fleet which might have been used to transport supplies for the invading army. It’s likely that the land force took the old ancient tracks used by the Romans, along the east coast of England, through Lothian and fording the River Forth near Stirling and into the heart of Scotland. Malcolm was said to have led the ships which landed at Dundee, and captured the fortress there and gathering Scottish rebels to his cause before sailing around Fife and into the River Tay and up to Birnam, where it is said he met with more Scots willing to join his cause, as Andrew Wyntoun, writing much later in the 15thc suggests with some plausibility.

The Northumbrian Chronicles account, is more colourful than the Worcester Chronicle and describes a huge invading force by the standards of the day. It is not known where Siward and Malcolm met up, it could have been at Dundee or perhaps Birnam or Stirling even. As they marched through the plains of Gowrie on their way past Scone, they would have most likely used the tactics often used in medieval warfare, probably raping and pillaging to draw Macbeth out of his lair to face them. Macbeth would have needed a much larger army than he would have kept in his household and it could be that in order to muster such forces he would need to ride the country to do so.

The campaign of Siward and Malcolm culminated in one of the most massive battles in 11thc Scotland. Malcolm and Siward’s forces were said to have approached from Birnam wood at night, under the cover of tree branches that they carried to disguise them, which was later immortalised by Shakespeare in his play Macbeth.

“Macbeth shall never vanquished be,

Until great Birnam Wood, to High Dunsinane Hill,

Shall Come against Him.”MacBeth, Act 3, Scene 1

William Shakespeare

Whether or not Malcolm and Siward’s tactics of attrition had the desired affect of drawing Macbeth out of his fortress, identified as Dunsinane, is not known, however Macbeth’s forces charged down from the hills at the combined Northumbrian and Scottish army and were put to flight by the invaders. It was a hard fought battle and the annals of Ulster record as many as 3000 Scottish dead, 1500 English dead, but Macbeth escaped, so it was a semi-victory for Siward and Malcolm for Macbeth went on after this, his power greatly reduced by the battle, but remained ‘king in the north’ to coin the phrase from Game of Thrones, but not used contemporarily.

The surviving English forces returned overloaded with booty, probably acquisitions gained from their pillaging and perhaps the capture of Dundee. Siward deposited Malcolm, inaugurated as King of the Scots in firm control of the Lowlands with his Scottish supporters. Having been away from Scotland for so long, this young man must have seemed more English than Scottish to his new subjects and it was to take him three more years before he was to finally consolidate his power fully, after hunting down Macbeth, who cannot be said to have skulked in his hideaway but worked hard to maintain his power further north and spent the next three years of his life, in his early fifties, an old man in Dark Age terms, carrying out ambitious raids deep into the lowlands.

In 1057 Malcolm Canmore, successfully lead a force across the Grampian mountains and lay an ambush for the unsuspecting Macbeth, at the village of Lumphanon, deep in Moray, as he returned from a southern foray. Macbeth was slain in the battle. Rebels after that placed Macbeth’s stepson, Lulach, in power following Macbeth’s death, but he too was executed also, ensuring no rivals were left, or brave enough, to oppose Malcolm’s rule.

Eerily, Macbeth’s death came on the exact same date of August the 16th as that of Malcolm’s father, Duncan.

Why was this little known 11th century battle a game changer for both English and Scottish history?

In 1066, after the conquest of England by the Norman duke, William, Anglo-Saxon nobility was mostly decimated on the field of Hastings and the continued conflicts that followed. Wives and orphans of those slaughtered were displaced and in came the new ruling class. The royal family was now Norman, and the last remaining prince of the English royal house of Wessex, Edgar, briefly crowned by the survivors of the witan, was prevented from keeping his crown when he was taken hostage by William who then usurped him.

Edgar eventually managed to escape William and he and his sister, Margaret fled to Scotland and were harboured by Macbeth’s replacement, Malcolm Canmore, who by this time had been king for around ten years or so. Malcolm was taken by the very devout Margaret and eventually they were married and their daughter, Edith, went on to marry William the Conqueror’s successor and son, Henry I, and became Queen Matilda.

This meant that the English line of Wessex had returned to the English royal family and also flowed in the blood of Malcolm Canmore’s children thus uniting the two kingdoms through blood and bringing Anglo-Saxon culture to Scotland with both Malcolm and Margaret. The old Gaelic bloodline of the House of Alpin was now replaced by the House of Dunkeld whose outlook was very much influenced by the Anglo-Saxons. Equally it meant that there was also Scottish influence now in the English royal bloodline.

Tragically, MacBeth’s defeat at Dunsinane, led to his eventual removal from the Scottish throne, ending the Gaelic/Pictish influence and his successor, Malcolm’s, look to England to found his new Anglo-Scottish dynasty, (of course with a smattering of Germano/Hungarian).

References

Abingdon version of the Anglo Saxon Chronicle

Aitcheson, N 1999 Macbeth, Man and Myth Sutton Publishing LTD, Phoenix Hill, Gloucestershire

Symeon of Durham – Historia Regum.

The Northumbrian Chronicles.

To keep up with the rest of the Blog Hop see whose next here.

Tomorrow we visit the blog of Cathie Dunn at https://cathiedunn.blogspot.com/